How crazy am I to think

I actually know where

that Malaysia Airlines plane is?*

* Kinda crazy. (But also maybe right?)

In the year since the vanishing of MH370, I appeared on CNN more

than 50 times, watched my spouse’s eyes glaze over at dinner, and fell

in with a group of borderline-obsessive amateur aviation sleuths. A

million theories bloomed, including my own.

than 50 times, watched my spouse’s eyes glaze over at dinner, and fell

in with a group of borderline-obsessive amateur aviation sleuths. A

million theories bloomed, including my own.

Illustration by Ritterized

The unsettling oddness was there from the first moment, on

March 8, when Malaysia Airlines announced that a plane from Kuala Lumpur

bound for Beijing, Flight 370, had disappeared over the South China Sea

in the middle of the night. There had been no bad weather, no distress

call, no wreckage, no eyewitness accounts of a fireball in the sky—just a

plane that said good-bye to one air-traffic controller and, two minutes

later, failed to say hello to the next. And the crash, if it was a

crash, got stranger from there.

My yearlong detour to Planet MH370

began two days later, when I got an email from an editor at Slate

asking if I’d write about the incident. I’m a private pilot and science

writer, and I wrote about the last big mysterious crash, of Air France 447 in 2009. My story ran on the 12th. The following morning, I was invited to go on CNN. Soon, I was on-air up to six times a day as part of its nonstop MH370 coverage.

There was no intro course on how to be a cable-news expert. The Town

Car would show up to take me to the studio, I’d sign in with reception, a

guest-greeter would take me to makeup, I’d hang out in the greenroom,

the sound guy would rig me with a mike and an earpiece, a producer would

lead me onto the set, I’d plug in and sit in the seat, a producer would

tell me what camera to look at during the introduction, we’d come back

from break, the anchor would read the introduction to the story and then

ask me a question or maybe two, I’d answer, then we’d go to break, I

would unplug, wipe off my makeup, and take the car 43 blocks back

uptown. Then a couple of hours later, I’d do it again. I was spending 18

hours a day doing six minutes of talking.

As

time went by, CNN winnowed its expert pool down to a dozen or so

regulars who earned the on-air title “CNN aviation analysts”: airline

pilots, ex-government honchos, aviation lawyers, and me. We were paid by

the week, with the length of our contracts dependent on how long the

story seemed likely to play out. The first couple were seven-day, the

next few were 14-day, and the last one was a month. We’d appear solo, or

in pairs, or in larger groups for panel discussions—whatever it took to

vary the rhythm

of perpetual chatter.Most notable: The segment in which Don Lemon

floated the possibility that MH370 had been sucked into a black hole. A

screen shot that included my face flashed onscreen during a Jon Stewart

segment eviscerating CNN’s coverage. This represents my media apotheosis

to date. [video]

I soon realized the germ of every TV-news segment is: “Officials say

X.” The validity of the story derives from the authority of the source.

The expert, such as myself, is on hand to add dimension or clarity.

Truth flowed one way: from the official source, through the anchor, past

the expert, and onward into the great sea of viewerdom.

What made MH370 challenging to cover was, first, that the event was unprecedented and technically complex and, second, that the officials were remarkably untrustworthy.

For instance, the search started over the South China Sea, naturally

enough, but soon after, Malaysia opened up a new search area in the

Andaman Sea, 400 miles away. Why? Rumors swirled that military radar had

seen the plane pull a 180. The Malaysian government explicitly denied

it, but after a week of letting other countries search the South China

Sea, the officials admitted that they’d known about the U-turn from day

one.

Of course, nothing turned up in the Andaman Sea, either. But in

London, scientists for a British company called Inmarsat that provides

telecommunications between ships and aircraft realized its database

contained records of transmissions between MH370 and one of its

satellites for the seven hours after the plane’s main communication

system shut down. Seven hours! Maybe it wasn’t a crash after all—if it

were, it would have been the slowest in history.Not that slow crashes

are unprecedented. In 2005, Helios Airways Flight 522 en route from

Cyprus to Athens lost cabin pressure and flew for nearly three hours

with unconscious pilots before the engines failed and it crashed.

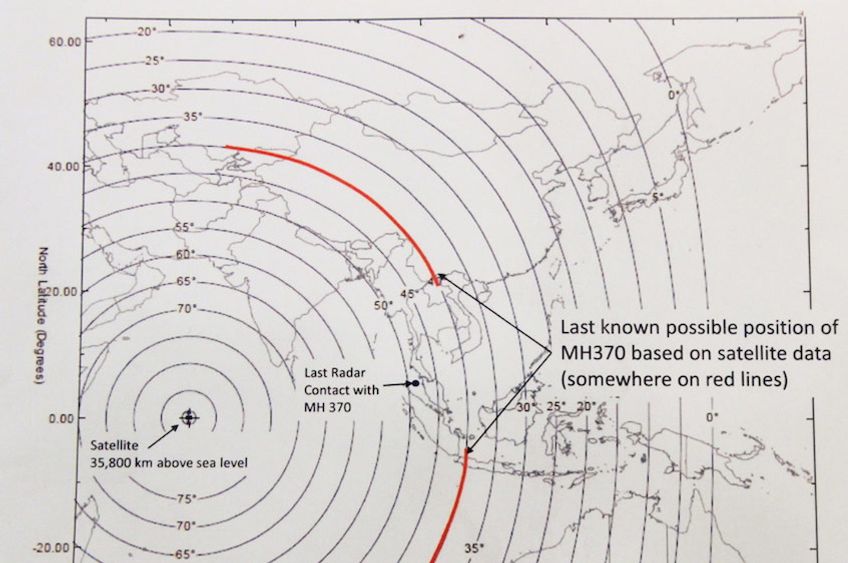

Photo: Government of Malaysia

These electronic “handshakes” or “pings” contained no actual

information, but by analyzing the delay between the transmission and

reception of the signal— called the burst timing offset, or BTO—Inmarsat

could tell how far the plane had been from the satellite and thereby

plot an arc along which the plane must have been at the moment of the

final ping.Fig. 3 That arc stretched some 6,000 miles, but if the plane

was traveling at normal airliner speeds, it would most likely have wound

up around the ends of the arc—either in Kazakhstan and China in the

north or the Indian Ocean in the south. My money was on Central Asia.

But CNN quoted unnamed U.S.-government sources saying that the plane had

probably gone south, so that became the

dominant view.Because the northern parts of the traffic corridor

include some tightly guarded airspace over India, Pakistan, and even

some U.S. installations in Afghanistan, U.S. authorities believe it more

likely the aircraft crashed into waters outside of the reach of radar

south of India, a U.S. official told CNN. If it had flown farther north,

it’s likely it would have been detected by radar. [article & video]

became internet-famous and spawned speculation the plane had wound up

there.

Other views were circulating, too, however.Fig. 5 A Canadian pilot named Chris Goodfellow went viral with his theory that MH370 suffered a fire that knocked out its communications gear and diverted from its planned route in order to attempt an emergency landing. Keith Ledgerwood, another pilot, proposed

that hijackers had taken the plane and avoided detection by ducking

into the radar shadow of another airliner. Amateur investigators pored

over satellite images, insisting that wisps of cloud or patches of

shrubbery were the lost plane. Courtney Love, posting on her Facebook time line a picture of the shimmering blue sea, wrote: “I’m no expert but up close this does look like a plane and an oil slick.”Fig. 6

Fig. 6.

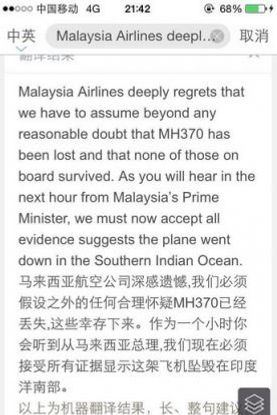

Then: breaking news! On March 24, the Malaysian prime minister, Najib

Razak, announced that a new kind of mathematical analysis proved that

the plane had in fact gone south. This new math involved another aspect

of the handshakes called the burst frequency offset, or BFO, a measure

of changes in the signal’s wavelength, which is partly determined by the

relative motion of the airplane and the satellite. That the whole

southern arc lay over the Indian Ocean meant that all the passengers and

crew would certainly be dead by now. This was the first time in history

that the families of missing passengers had been asked to accept that their loved ones were dead

because a secret math equation said so. Fig. 7 Not all took it well. In

Beijing, outraged next-of-kin marched to the Malaysian Embassy, where

they hurled water bottles and faced down paramilitary soldiers in riot

gear.

Fig. 7. Making matters worse, the Malaysians informed some of the passengers by text message.

123,000-square-mile patch of ocean west of Perth. Ships and planes

found much debris on the surface, provoking a frenzy of BREAKING NEWS

banners, but all turned out to be junk. Adding to the drama was a

ticking clock. The plane’s two black boxes had an ultrasonic sound

beacon that sent out acoustic signals through the water. (Confusingly,

these also were referred to as “pings,” though of a completely different

nature. These new pings suddenly became the important ones.) If

searchers could spot plane debris,

they’d be able to figure out where the plane had most likely gone down,

then trawl with underwater microphones to listen for the pings. The problem was that the pingers had a battery life of only 30 days.

On April 4, with only a few days’ pinger life remaining, an

Australian ship lowered a special microphone called a towed pinger

locator into the water.Fig. 8 Miraculously, the ship detected four

pings. Search officials were jubilant, as was the CNN greenroom.

Everyone was ready for an upbeat ending.

Fig. 8.

Photo: Government of Malaysia

The only Debbie Downer was me. I pointed out that the pings were at

the wrong frequency and too far apart to have been generated by

stationary black boxes. For the next two weeks, I was the odd man out on

Don Lemon’s six-guest panel blocks, gleefully savaged on-air by my

co-experts.

The Australians lowered an underwater robotFig. 9 to scan the seabed

for the source of the pings. There was nothing. Of course, by the rules

of TV news, the game wasn’t over until an official said so. But things

were stretching thin. One night, an underwater-search veteran taking

part in a Don Lemon panel agreed with me that the so-called

acoustic-ping detections had to be false. Backstage after the show, he

and another aviation analyst nearly came to blows. “You don’t know what

you’re talking about! I’ve done extensive research!” the analyst

shouted. “There’s nothing else those pings could be!”

Fig. 9.

Photo: Bluefin Robotics

Soon after, the story ended the way most news stories do: We just

stopped talking about it. A month later, long after the caravan had

moved on, a U.S. Navy officer said publicly that the pings had not come

from MH370. The saga fizzled out with as much satisfying closure as the final episode of Lost.

The Search for MH370

on Inmarsat orbital mechanics on his website.Fig. 10 The comments

section quickly grew into a busy forum in which technically

sophisticated MH370 obsessives answered one another’s questions and

pitched ideas. The open platform attracted a varied crew, from the

mostly intelligent and often helpful to the deranged and abusive.

Eventually, Steel declared that he was sick of all the insults and shut

down his comments section. The party migrated over to my blog, jeffwise.net.

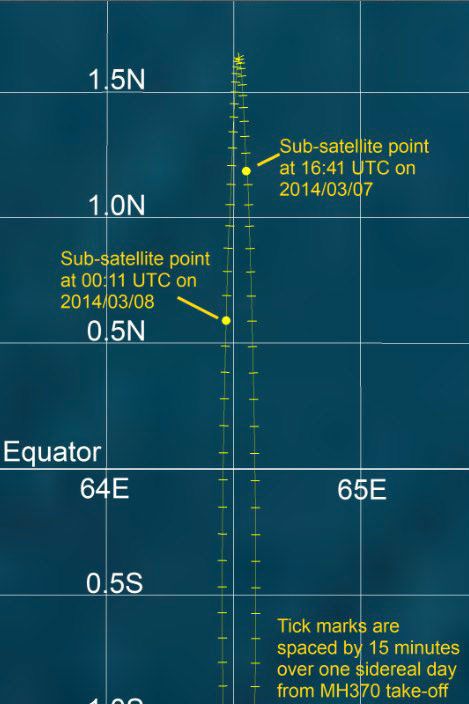

satellite that MH370 was communicating with, 3F-1, was not truly

geostationary but wobbled in its orbit, a crucial detail upon which the

whole story would turn out to hinge. This image shows the path the

satellite took during MH370’s final six hours.

Meanwhile, a core of engineers and scientists had split off via group

email and included me. We called ourselves the Independent Group,Member

roster: Brian Anderson, Sid Bennett, Curon Davies, Pierre-Michel

Decombeix, Michael Exner, Tim Farrar, Yap Fook Fah, Richard Godfrey, Bob

Hall, Bill Holland, Geoff Hyman, Victor Iannello, Barry Martin, L. Rand

Mayer, Henrik Rydberg, Duncan Steel, Don Thompson, and me. or IG. If

you found yourself wondering how a satellite with geosynchronous orbit

responds to a shortage of hydrazine, all you had to do was ask.Answer:

It starts to wobble, creating an error in the frequency of received

signals from which scientists can later attempt to extract clues about

an airplane’s motion. The IG’s first big break came in late May, when

the Malaysians finally released the raw Inmarsat data.

By combining the data with other reliable information, we were able to

put together a time line of the plane’s final hours: Forty minutes after

the plane took off from Kuala Lumpur, MH370 went electronically dark.

For about an hour after that, the plane was tracked on radar following a

zigzag course and traveling fast. Then it disappeared from military

radar. Three minutes later, the communications system logged back onto

the satellite. This was a major revelation. It hadn’t stayed connected,

as we’d always assumed. This event corresponded with the first satellite

ping. Over the course of the next six hours, the plane generated six

more handshakes as it moved away from the satellite.

The final handshake wasn’t completed. This led to speculation that

MH370 had run out of fuel and lost power, causing the plane to lose its

connection to the satellite. An emergency power system would have come

on, providing enough electricity for the satcom to start reconnecting

before the plane crashed. Where exactly it would have gone down down was

still unknown—the speed of the plane, its direction, and how fast it

was climbing were all sources of uncertainty.

The MH370 obsessives continued attacking the problem. Since I was the

proprietor of the major web forum, it fell on me to protect the fragile

cocoon of civility that nurtured the conversation. A single troll could

easily derail everything. The worst offenders were the ones who seemed

intelligent but soon revealed themselves as Believers. They’d seized on a

few pieces of faulty data and convinced themselves that they’d

discovered the truth. One was sure the plane had been hit by lightning

and then floated in the South China Sea, transmitting to the satellite

on battery power. When I kicked him out, he came back under aliases. I

wound up banning anyone who used the word “lightning.”

By October, officials from the Australian Transport Safety Board had

begun an ambitiously scaled scan of the ocean bottom, and, in a

surprising turn, it would include the area suspected by

the IG.The Independent Group had published a formal analysis of the

signals incorporating research we’d done into aircraft performance and

autopilot modes. We’d wound up concluding that the official search area

at the time was hundreds of miles off. [pdf] For those who’d been a

part of the months-long effort, it was a thrilling denouement. The

authorities, perhaps only coincidentally, had landed on the same

conclusion as had a bunch of randos from the internet. Now everyone was

in agreement about where to look.

While jubilation rang through the email threads, I nursed a

guilty secret: I wasn’t really in agreement. For one, I was bothered by

the lack of plane debris. And then there was the data. To fit both the

BTO and BFO data well, the plane would need to have flown slowly, likely

in a curving path. But the more plausible autopilot settings and known

performance constraints would have kept the plane flying faster and more

nearly straight south. I began to suspect that the problem was with the

BFO numbers—that they hadn’t been generated in the way we

believed.Others were having doubts, too, including Tim Clark, the

presidents of Emirates Airlines, which operates more 777s than any other

company in the world. “We have not seen a single thing that suggests

categorically that this aircraft is where they say it is,” Clark said in

an interview with Der Spiegel. If that were the case, perhaps the flight had gone north after all.

For a long time, I resisted even considering the possibility that

someone might have tampered with the data. That would require an almost

inconceivably sophisticated hijack operation, one so complicated and

technically demanding that it would almost certainly need state-level

backing. This was true conspiracy-theory material.

And yet, once I started looking for evidence, I found it. One of the

commenters on my blog had learned that the compartment on 777s called

the electronics-and-equipment bay, or E/E bay, can be accessed via a

hatch in the front of the first-class cabin.You can see how easily in this video. [youtube]

If perpetrators got in there, a long shot, they would have access to

equipment that could be used to change the BFO value of its satellite

transmissions. They could even take over the

flight controls.Incredibly, an Australian graduate student named Matt

Wuillemin had recognized the potential the hatch presented for hijackers

and tried to warn authorities. He was ignored. [pdf]

I realized that I already had a clue that hijackers had been in the

E/E bay. Remember the satcom system disconnected and then rebooted three

minutes after the plane left military radar behind. I spent a great

deal of time trying to figure out how a person could physically turn the

satcom off and on. The only way, apart from turning off half the entire

electrical system, would be to go into the E/E bay and pull three

particular circuit breakers. It is a maneuver that only a sophisticated

operator would know how to execute, and the only reason I could think

for wanting to do this was so that Inmarsat would find the records and

misinterpret them. They turned on the satcom in order to provide a false

trail of bread crumbs leading away from the plane’s true route.

It’s not possible to spoof the BFO data on just any plane. The plane

must be of a certain make and model, Has to be one of the newer models

of Boeing; in Airbus jets the E/E bay hatch is inaccessible from the

passenger cabin, and older Boeing planes lack the ability to

autoland.equipped with a certain make and model of

satellite-communications equipment,A crucial piece of satcom hardware,

the satellite data unit, must be built by Honeywell/Thales, not its

competitor, Raytheon, for this to work. and flying a certain kind of

routeOne that begins near the equator and heads in a direction opposite

to a large body of water. in a region covered by a certain kind of

Inmarsat satellite.One that is running low on fuel. If you put all the

conditions together, it seemed unlikely that any aircraft would satisfy

them. Yet MH370 did.

I imagine everyone who comes up with a new theory, even a complicated

one, must experience one particularly delicious moment, like a perfect

chord change, when disorder gives way to order. This was that moment for

me. Once I threw out the troublesome BFO data, all the inexplicable

coincidences and mismatched data went away. The answer became

wonderfully simple. The plane must have gone north.

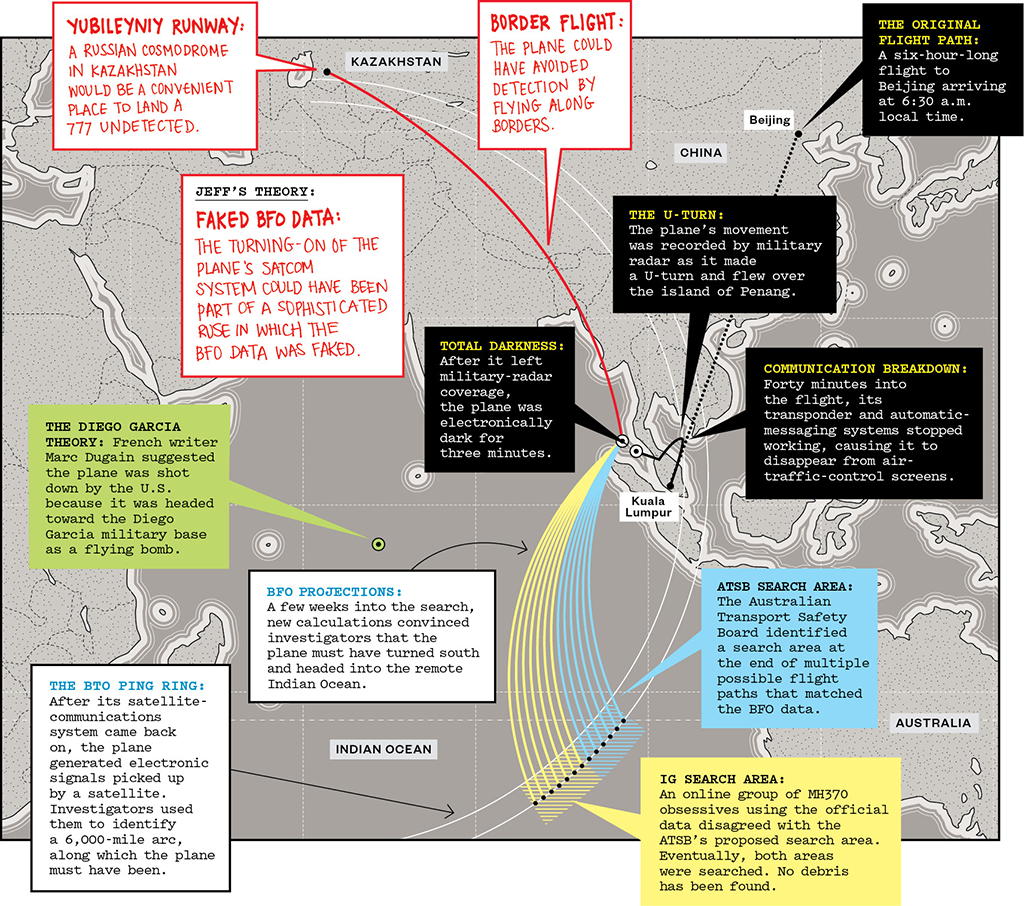

Using the BTO data set alone, I was able to chart the plane’s speed

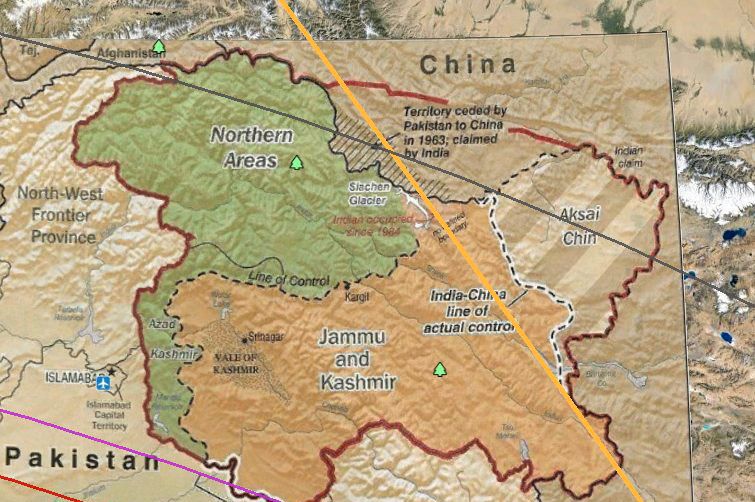

and general path, which happened to fall along national borders.Fig. 21

Flying along borders, a military navigator told me, is a good way to

avoid being spotted on radar. A Russian intelligence plane nearly

collided with a Swedish airliner while doing it over the Baltic Sea in

December. If I was right, it would have wound up in Kazakhstan, just as

search officials recognized early on.

Fig. 21. In particular, the flight path skirts the border of

China and just misses the disputed and much-watched India-Pakistan

border.

Fig. 22.

Photo: Jeff Wise

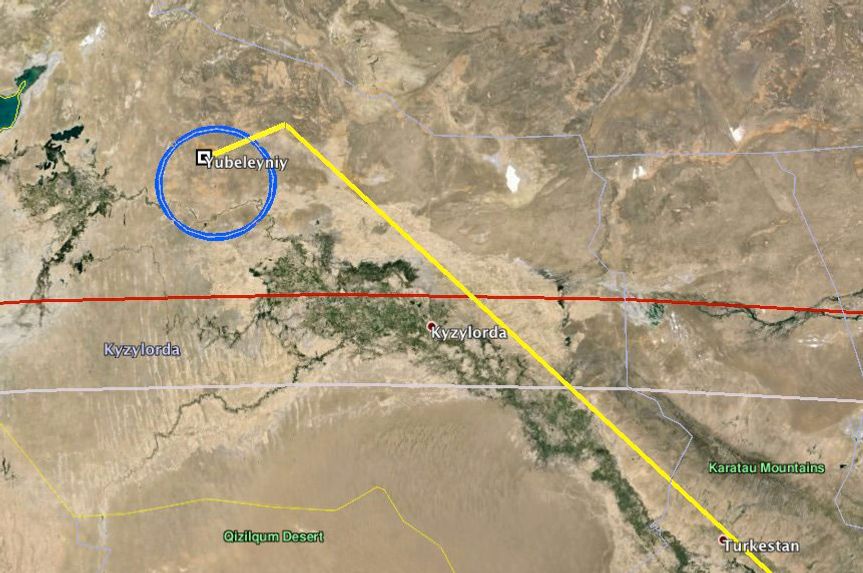

There aren’t a lot of places to land a plane as big as the 777, but,

as luck would have it, I found one: a place just past the last handshake

ring called Baikonur Cosmodrome.Fig. 22 Baikonur is leased from

Kazakhstan by Russia. A long runway there called Yubileyniy was built

for a Russian version of the Space Shuttle. If the final Inmarsat ping

rang at the start of MH370’s descent, it would have set up nicely for an

approach to Yubileyniy’s runway 24.

the only one in the world built specifically for self-landing airplanes.

The 777, which was developed in the ’90s, has the ability to autoland.

From a hijacking perspective, this feature allows people who don’t have

commercial-piloting experience to abscond with an airplane and get it

safely on the ground, so long as they know what autopilot settings to

input.

If MH370 did land at Yubileyniy, it had 90 minutes to

either hide or refuel and takeoff again before the sun rose. Hiding

would be hard. This part of Kazakhstan is flat and treeless, and there

are no large buildings nearby. The complex has been slowly crumbling for

decades, with satellite images taken years apart showing little change,

until, in October, 2013, a disused six-story building began to be

dismantled. Next to it appeared a rectangle of bulldozed dirt with a

trench at one end.

before the following image was taken on January 9, 2014, the temperature

fluctuated between -15F and +14F.

Construction

experts told me these images most likely show site remediation: taking

apart a building and burying the debris. Yet why, after decades, did the

Russians suddenly need to clear this one lonely spot, in the heart of a

frigid winter, finishing just before MH370 disappeared?

Kazakhstan, my suspicion fell on Russia. With technically advanced

satellite, avionics, and aircraft-manufacturing industries, Russia was a

paranoid fantasist’s dream.At the time of MH370’s disappearance, he had

just used special forces to annex Crimea and was running civil war by

proxy in eastern Ukraine via military intelligence. (The Russians, or at

least Russian-backed militia, were also suspected in the downing of

Malaysia Flight 17 in July.) Why, exactly, would Putin want to steal a

Malaysian passenger plane? I had no idea. Maybe he wanted to demonstrate

to the United States, which had imposed the first punitive sanctions on Russia

the day before, that he could hurt the West and its allies anywhere in

the world. Maybe what he was really after were the secrets of one of the

plane’s passengers.Aboard the flight were 20 employees of Freescale

Semiconductor, which develops processors and sensors for the “Internet

of Things.” Maybe there was something strategically crucial in the hold.

Or maybe he wanted the plane to show up unexpectedly somewhere someday,

packed with explosives. There’s no way to know. That’s the thing about

MH370 theory-making: It’s hard to come up with a plausible motive for an

act that has no apparent beneficiaries.

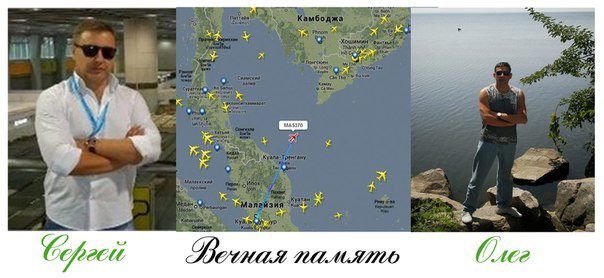

As it happened, there were three ethnically Russian men aboard MH370,

two of them Ukrainian-passport holders from Odessa.All were in their

mid-40s, old enough to be experienced, young enough for vigorous

action—about the same age as the military-intelligence officer who was

running the show in eastern Ukraine. Could any of these men, I wondered, be special forces or covert operatives?

As I looked at the few pictures available on the internet, they

definitely struck me as the sort who might battle Liam Neeson in midair.

Fig. 27. I was later able to confirm that they worked for

Nika-Mebel, an Odessa furniture company that sells online only, accepts

only cash payment, provides no landline number or address, and had no

content on its website before 2013. Both Nika-Mebel and the men’s

families refused to talk to me. This picture of the men was posted by a

friend on VK.com, the Russian version of Facebook.

About the two Ukrainians, almost nothing was available online.Fig. 27

I was able to find out a great deal about the Russian,Fig. 28 who was

sitting in first class about 15 feet from the E/E-bay hatch.Fig. 29 He

ran a lumber company in Irkutsk, and his hobby was technical diving

under the ice of Lake Baikal.His dive club’s annual New Year’s party under the ice. [video]

I hired Russian speakers from Columbia University to make calls to

Odessa and Irkutsk, then hired researchers on the ground.When MH17 was

shot down, it seemed to so perfectly tie the bow between the Ukraine war

and the other Malaysia Airlines 777 that I was terrified I’d gotten my

freelancer in Irkutsk in deep trouble; I texted her, and she replied

that she was fine. She didn’t seem concerned.

Fig. 28.

The more I discovered, the more coherent the story seemed to me.In fact, I wrote the whole thing up in an e-book, The Plane That Wasn’t There: Why We Haven’t Found MH370. [amazon]

I found a peculiar euphoria in thinking about my theory, which I

thought about all the time. One of the diagnostic questions used to

determine whether you’re an alcoholic is whether your drinking has

interfered with your work. By that measure, I definitely had a problem.

Once the CNN checks stopped coming, I entered a long period of intense

activity that earned me not a cent. Instead, I was forking out my own

money for translators and researchers and satellite photos. And yet I

was happy.

Fig. 29. At position B. The Ukrainians were at D and C—underneath the satellite antenna.

Photo: Seatguru

Still, it occurred to me that, for all the passion I had for my

theory, I might be the only person in the world who felt this way.

Neurobiologist Robert A. Burton points out in his book On Being Certain

that the sensation of being sure about one’s beliefs is an emotional

response separate from the processing of those beliefs. It’s something

that the brain does subconsciously to protect itself from wasting

unnecessary processing power on problems for which you’ve already found a

solution that’s good enough. “ ‘That’s right’ is a feeling you get so

that you can move on,” Burton told me. It’s a kind of subconscious

laziness. Just as it’s harder to go for a run than to plop onto the

sofa, it’s harder to reexamine one’s assumptions than it is to embrace

certainty. At one end of the spectrum of skeptics are scientists, who by

disposition or training resist the easy path; at the other end are

conspiracy theorists, who’ll leap effortlessly into the sweet bosom of

certainty. So where did that put me?

Propounding some new detail of my scenario to my wife over dinner one

night, I noticed a certain glassiness in her expression. “You don’t

seem entirely convinced,” I suggested.

She shrugged.

“Okay,” I said. “What do you think is the percentage chance that I’m right?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “Five percent?”I recently reminded her of

this conversation. “I was trying to be nice,” she said. What she really

thought was, Zero.

Springtime came to the southern ocean, and search vessels

began their methodical cruise along the area jointly identified by the

IG and the ATSB, dragging behind it a sonar rig that imaged the seabed

in photographic detail. Within the IG, spirits were high. The discovery

of the plane would be the triumphant final act of a remarkable underdog

story.

By December, when the ships had still not found a thing, I felt it

was finally time to go public. In six sequentially linked pages that

readers could only get to by clicking through—to avoid anyone reading

the part where I suggest Putin masterminded the hijack without first

hearing how I got there—I laid out my argument. I called it “The Spoof.”

I

got a respectful hearing but no converts among the IG. A few sites

wrote summaries of my post. The International Business Times headlined

its story “MH370: Russia’s Grand Plan to Provoke World War III, Says

Independent Investigator” and linked directly to the Putin part.

Somehow, the airing of my theory helped quell my obsession. My gut still

tells me I’m right, but my brain knows better than to trust my gut.

Last month, the Malaysian government declared that the aircraft is considered to have crashed and all those aboard are presumed dead.

Malaysia’s transport minister told a local television station that a

key factor in the decision was the fact that the search mission for the

aircraft failed to achieve its objective. Meanwhile, new theories are

still being hatched. One, by French writer Marc Dugain, states

that the plane was shot down by the U.S. because it was headed toward

the military bases on the islands of Diego Garcia as a flying bomb.His

scenario ignores the ping rings entirely.

The search failed to deliver the airplane, but it has accomplished

some other things: It occupied several thousand hours of worldwide

airtime; it filled my wallet and then drained it; it torpedoed the idea

that the application of rationality to plane disasters would inevitably

yield ever-safer air travel. And it left behind a faint, lingering itch

in the back of my mind, which I believe will quite likely never go away.

Jeff Wise is the author of The Plane That Wasn’t There

*This article appears in the February 23, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.

-- NYMag

Booking Buddy is the best travel search website, that you can use to compare travel deals from all large travel booking websites.

ReplyDelete